For instance, the CDC cannot officially report a COVID-19 death until the death certificate has been submitted and processed with the agency-a process that can take weeks-which means that the agency’s validated COVID-19 mortality stats don’t align with the states’ stats. Plus, federal agencies are often the last stop on the information pipeline, leading to reporting delays and discrepancies. Cases by nursing home facility? Head over to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Want to see death trends among seniors? Dig around the CDC site.

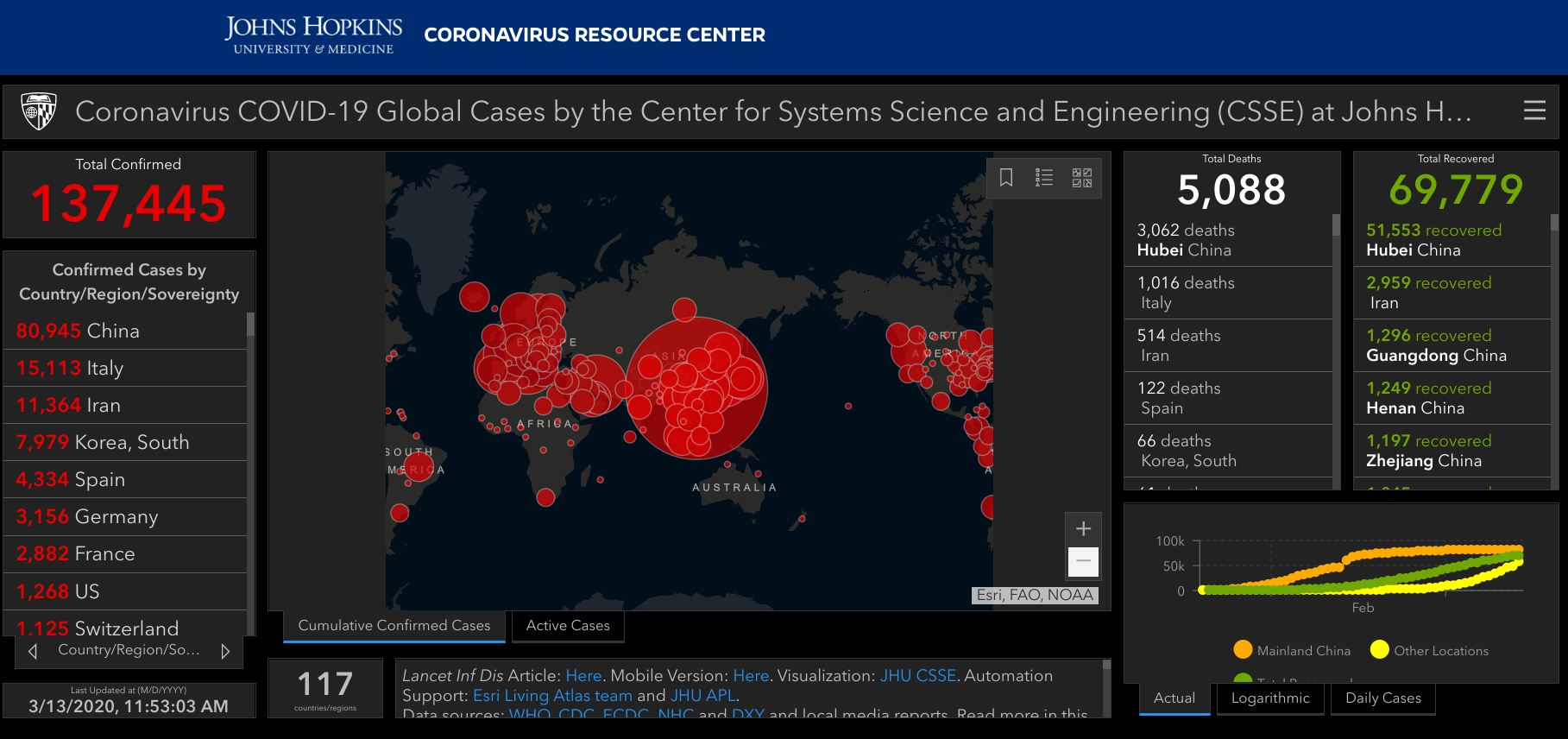

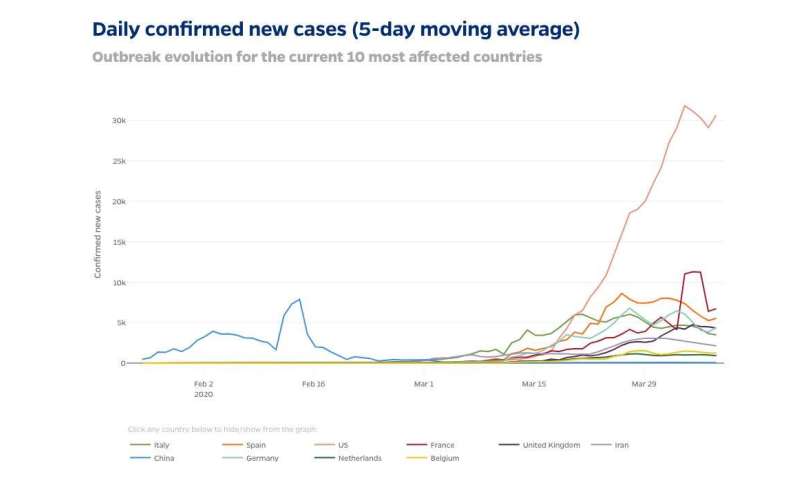

But the public must weed through nationwide data to find their community-if they know where to look. Some are still being reported at the federal level. Not all of the metrics have disappeared completely. Gardner and other members of the JHU team are dismayed by the reversal. states are consciously removing information or shutting down their dashboards entirely. That’s not because the websites are crashing from traffic overload, but because some U.S. coronavirus data have become harder to find or completely unavailable. Disappearing dataīut it’s a fragile system. Today, the people trust, and even take for granted, that timely, detailed and nicely packaged information is available at the tap of a screen. As these dashboards proliferated, they reset the public’s expectations for what health data should look like. states and cities, as well as other organizations and universities followed suit. agencies like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) eventually launched their own robust COVID-19 data websites simple enough for any teenager, grandparent or armchair statistician to dive into. “We put it out there in a way that was just so easy to interpret.” “People were so desperate for information,” recalls Gardner.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)